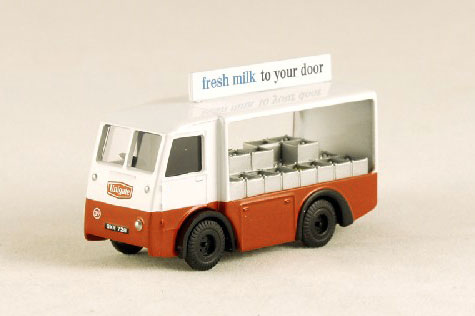

Reginald T. Weathers drives a milk float. He delivers milk all across the village every morning, and while doing so he helps his neighbours with their adventures. He has a moustache and a dog named Sprat. He doesn’t wear a seatbelt.

The children’s programme had been on television for almost forty years, repeated through three generations, etched deeply into the collective conscious of the country.

The state broadcaster, after scheduling repeats of the programme for the thirty-eighth consecutive year, was brought to task by the Road Safety Authority in a letter to newspapers. “While we acknowledge that The Rounds of Reginald T. Weathers was produced during less safety-conscious times, we do not think it is appropriate for children of a young age to be introduced to a character who so flagrantly ignores life saving seatbelt laws.”

The broadcaster backed down immediately—replying with a polite shrug of a letter—and replaced the programme with an imported Japanese cartoon advertising a trading card game.

Public opinion exploded, most likely because the interaction played out in the opinions page of a well-read newspaper. Had the afternoon broadcast of The Rounds of Reginald T. Weathers been quietly replaced by Ping-Weep after closed-door negotiations, it’s unlikely that many adults would have noticed.

Counter letters ensued, most mourning the death of a valued cultural icon at the behest of “health and safety gone mad”. Nobody was denying the value of seatbelts, but it seemed absurd to quash an enduring television programme over such a small offence. A motor historian wrote to say that milk floats of that era were usually not equipped with seatbelts, as they never reached speeds high enough to cause ejection in a crash. Requiring seatbelts in a milk float, she wrote, was like “demanding that pirates in pirate stories wear life jackets”.

The Milk FloatOne contributor asked whether it was possible that the seatbelt be digitally added to Reginald’s van, allowing him to deliver milk in a vehicle that met with modern standards. The production company responded at this point, noting that, while alteration to the footage was quite difficult, as the series was filmed in stop-motion with models rather than a straightforward animation, it would be technically possible to do so. However, the series creator had been missing, presumed dead, in Peru for that last three years, and any licensing or production changes to The Rounds of Reginald T. Weathers had to be approved by him. Since he was not officially dead yet, rather presumed, alteration rights had not passed back to the production company, and so they were only entitled to offer the programme in its existing form until the matter had been resolved.

The Milk FloatOne contributor asked whether it was possible that the seatbelt be digitally added to Reginald’s van, allowing him to deliver milk in a vehicle that met with modern standards. The production company responded at this point, noting that, while alteration to the footage was quite difficult, as the series was filmed in stop-motion with models rather than a straightforward animation, it would be technically possible to do so. However, the series creator had been missing, presumed dead, in Peru for that last three years, and any licensing or production changes to The Rounds of Reginald T. Weathers had to be approved by him. Since he was not officially dead yet, rather presumed, alteration rights had not passed back to the production company, and so they were only entitled to offer the programme in its existing form until the matter had been resolved.

Irate nostalgists began to upload entire episodes of the television programme to various video hosting sites on the Internet. These episodes were shared across social networking sites in a million tiny acts of rebellion, raising the profile of the cancellation even further. The online episodes were soon brought down, however, by the deployment of routine copyright protection letters by the production company’s lawyers. The video sites deleted the episodes, more were uploaded, and these in turn were deleted. In their agitated state of awareness, most social network activists took this to be a further sign of censorship on the part of the “health and safety”, rather than the standard removal of copyrighted content that is common practice for well-established video hosting websites.

Tempers burned feverishly. A small gathering was filmed outside the Road Safety Authority’s central offices near government buildings. The gathering protested loudly with signs and megaphones, many dressed as the characters that inhabited the world of Reginald T. Weathers. It was reported widely in the media over the following days. The Road Safety Authority issued no statement—they had been almost silent in the debate since sending their original letter to the papers.

Police reported a marked increase in traffic stops for drivers not wearing seatbelts. Instead of contrition, they were met with retorts about “health and safety” and general anger over the lack of respect for the country’s cultural heritage, usually somewhat more crudely articulated.

Public opinion railed against an amorphous authoritarian system. It was impossible to hold anyone to account. The production company shrugged, miming tied hands. The state broadcaster was a monolith, historically bound to protect its young audience from themselves. The Roads Safety Authority was a zealot with no interest in cultural questions outside its remit, and so in a way beyond reproach.

Most of the adults never watched broadcasts of The Rounds of Reginald T. Weathers, and had not seen the programme in years. Their children, moreover, had never seen a milk float. They were unfamiliar with the concept of home-delivered milk, and had never tasted creamery milk in their lives. The small, local villages of the type depicted in Reginald’s travels had been systematically dismantled over the previous forty years. In the ultimate service of health and safety, roads had been improved and widened. Footpaths had been installed, lamps erected, roundabouts laid, pedestrian crossings situated, and ditches and stone walls removed to make way. Many other changes had altered the landscape since the production of The Rounds, most in service of the comfort and ease of the protesting adults. Out-of-town retail centres had replaced the small, limited village shops inhabited and frequented by Reginald’s neighbours. Large, spacious apartments and houses with generous parking skirted the new outskirts of towns and villages, hiding away fields and cows from the sides of roads. Fences were no longer hopped. Grass was no longer chewed.

The life of Reginald T. Weathers was archaic in both form and appearance. But he was not yet historical enough to escape the demands of a risk-averse society. His quaint village suffered the indignity of simultaneous irrelevance and controversy.

What were the adults trying to save? The world they once knew, or the world as they wished it existed? A representation of the world they were happy to let go? A relic or a guide? Why abandon the milk float, the milk, and then fight for the milkman?

Most children remained unaware of the one-sided debate raging above their heads. In the afternoons they watched Ping-Weep, and enjoyed it very much. For children do not mourn what is lost, even if it is valuable. This is both their great strength and their great weakness. They do not miss Reginald. They do not miss neighbours, or hopped fences, or milk.